Tomorrow morning, the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences will announce their nominations for the Academy Awards, honoring the work of films released in 2011.

For over a decade, I've made it my business to attempt to predict which films and performances would garner Oscar nominations, as the film award season has been a great hobby of mine going back as far as I can remember. I'd like to think that I got pretty good at making predictions, too, considering my lack of access as simply a passionate, serious film-lover (and not a professional award season writer). I would read books about how to predict what would be nominated and what would win. I'd devise my own methods for making my choices.

But something I wrote in last year's predictions bears repeating today, and that is the fact that the prevalence of award season blogs and insider information has actually made my job a little less fun and, in many ways, less difficult. Whereas I once had to watch each film and guess what I thought the Academy would support, I now simply have to read five or six trusted sources online and then can shoot down the middle with my predictions, using a law of averages. It's certainly less mysterious today.

Some mystery has returned this year, however, with the rule change to allow the Best Picture category to fluctuate between five and 10 nominees, based on the support shown to each film via first place votes. I am almost certain that everything you'll see me predict here today will be nominated in this category; it's just a matter of how many. So I'll try to predict that number, too, and not award myself full credit for any over/under that.

The format I use for my nomination predictions is the same one I've used

for the past decade or so. I attempt to predict who will be nominated

in the "big" categories: Picture, Director and the four acting

categories. I predict the five nominees and provide two alternates that I

think could sneak in. I give myself a point for each one I get right

and a half-point for alternates. This used to total 40 points, but now

it will total 45 because of the expansion of the Best Picture race to 10

nominees. Then, I tack on what I call "The 10," which is a list of 10

random nominees from any of the other categories I feel certain will be

nominated.

BEST PICTURE

I make no genius statements here when I say that filling out the first five nominees - the minimum possible - is easy. I'm also no maverick in predicting that the Academy will likely take advantage of the new rule and nominate more than five. And, not straying in any way from the other prognosticators, I'm doubting that they will nominate a full slate of 10. So how many get in?

Well, I think the following are sure bets:

The Artist,

The Descendants,

The Help,

Hugo and

Midnight in Paris.

So that's five. I feel pretty good about adding

Moneyball as a sixth choice, as it will certainly score nominations for its screenplay and for Brad Pitt as actor.

But there's a part of me that says we'll see a seventh nominee, and possibly an eighth. If these slots happen at all, I predict that one of them will go to

The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo. The other will go to either

War Horse or

The Tree of Life. This leaves

Extremely Loud and Incredibly Close and

Bridesmaids as the supposed nine and 10 choices, with

Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy on the outside looking in. I don't need another alternate when I have this many on my list, but I'll throw

The Ides of March on there just to have one.

BEST DIRECTOR

I wasn't feeling certain before but am now feeling more confident that we'll here Woody Allen's name for his first nomination here since 1994's Bullets Over Broadway, and that makes me very happy!

My picks: Woody Allen (

Midnight in Paris), David Fincher (

The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo), Michel Hazanavicius (

The Artist), Alexander Payne (

The Descendants), Martin Scorsese (

Hugo)

My alternates: Terrence Malick (

The Tree of Life), Steven Spielberg (

War Horse)

Second guessing myself: There's only one guy on this list I'm not sure about at all, and that's Fincher. He was nominated last year, and he seems overdue for a win, though there's no chance in hell that can happen this year. The more I sit and think the more I feel like Malick could steal that slot.

The Tree of Life hasn't been high on people's nomination lists for months now, but I can't shake the feeling that it is a respected work of art as a film and that he'll be rewarded for it. I'm also a tad nervous to leave Stephen Daldry off the list, when every single one of his previous films (

Billy Elliot, The Hours, The Reader) has nabbed him a nomination here, but

Extremely Loud and Incredibly Close just doesn't seem like it ever got off the ground.

BEST ACTOR

My picks: George Clooney (

The Descendants), Jean Dujardin (

The Artist), Michael Fassbender (

Shame), Gary Oldman (

Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy), Brad Pitt (

Moneyball)

My alternates: Leonardo DiCaprio (

J. Edgar), Michael Shannon (

Take Shelter)

Second guessing myself: I think Clooney, Dujardin and Pitt are locks here. Though the NC-17 rating of

Shame might off-put some, I think Fassbender is one of the most talked about actors out there right now, and I think they'll welcome him to the club for this daring work, however difficult it is to watch. That leaves Oldman on shaky ground, but I've heard great things and he's overdue. Otherwise, the slot would be DiCaprio's. But

J. Edgar has fallen off the radar and most likely, so will he. Shannon seems like a good alternate for Fassbender, should the academy choose to elevate a daring, serious actor.

BEST ACTRESS

My picks: Glenn Close (

Albert Nobbs), Viola Davis (

The Help), Meryl Streep (

The Iron Lady), Tilda Swinton (

We Need To Talk About Kevin), Michelle Williams (

My Week With Marilyn)

My alternates: Just as everyone thought Kate Winslet would be nominated as a Supporting Actress for

The Reader a few years ago, I think Berenice Bejo could be nominated here for

The Artist instead of in the supporting category. Truthfully, this is the correct category for her because it's a leading performance and she's more than worthy of a nomination. Assuming she's placed in supporting where her studio wants her, the alternates are Rooney Mara (

The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo) and Elizabeth Olsen (

Martha Marcy May Marlene)

Second guessing myself: The Davis-Streep-Williams trifecta has been a foregone conclusion for what seems like months now, and most agree that Close will make it, as she was once a front-runner here. That leaves Swinton the most vulnerable but she's a past winner and brilliant in her film this year, which leads me to believe that unless the scenario I posed above happens, she's in instead of Mara, Olsen or Charlize Theron (in the underperforming

Young Adult). Kristin Wiig, another name being thrown around, will get a screenplay nomination for

Bridesmaids, not an acting one.

BEST SUPPORTING ACTOR

My picks: Kenneth Branagh (

My Week With Marilyn), Albert Brooks (

Drive), Jonah Hill (

Moneyball), Ben Kingsley (

Hugo), Christopher Plummer (

Beginners)

My alternates: Nick Nolte (

Warrior), Corey Stall (

Midnight in Paris)

Second guessing myself: They've all but handed this over to Plummer, and bravo to that. But I'm confident that he'll be joined by Brooks and Hill for playing so jarringly against type and Branagh for playing brilliantly within his wheelhouse. Kingsley was the emotional center of a film that stands a chance to garner the most overall nominations, so I'm going out on a limb and predicting he'll be swept in in place of the more frequently predicted Nolte. And as for Corey Stall, he's my one original, out-of-left-field prediction among everything here, and I had to have at least one. But when a Woody Allen film does as well as

Midnight in Paris is doing, an acting nomination tends to follow. And who is more memorable in the film than Stall as Hemingway? Nobody!

BEST SUPPORTING ACTRESS

My picks: Berenice Bejo (

The Artist), Jessica Chastain (

The Help), Melissa McCarthy (

Bridesmaids), Janet McTeer (

Albert Nobbs), Octavia Spencer (

The Help)

My alternates: Shailene Woodley (

The Descendants), Carey Mulligan (

Shame)

Second guessing myself: A lead nomination for Bejo moves Woodley in, but that'd be the only change in a category I feel very confident about.

THE TEN

Take these to the bank:

1. Original Screenplay: Woody Allen (

Midnight in Paris)

2. Adapted Screenplay: Steve Zaillian and Aaron Sorkin (

Moneyball)

3. Foreign Language Film:

A Separation (Iran)

4. Animated Feature:

Rango

5. Animated Feature:

The Adventures of Tintin

6. Art Direction:

Hugo

7. Cinematography: Emmanuel Lubezki (

The Tree of Life)

8. Film Editing: Anne-Sophie Bion (

The Artist)

9. Original Score: Ludovic Bource (

The Artist)

10. Original Song: "The Living Proof" (

The Help)

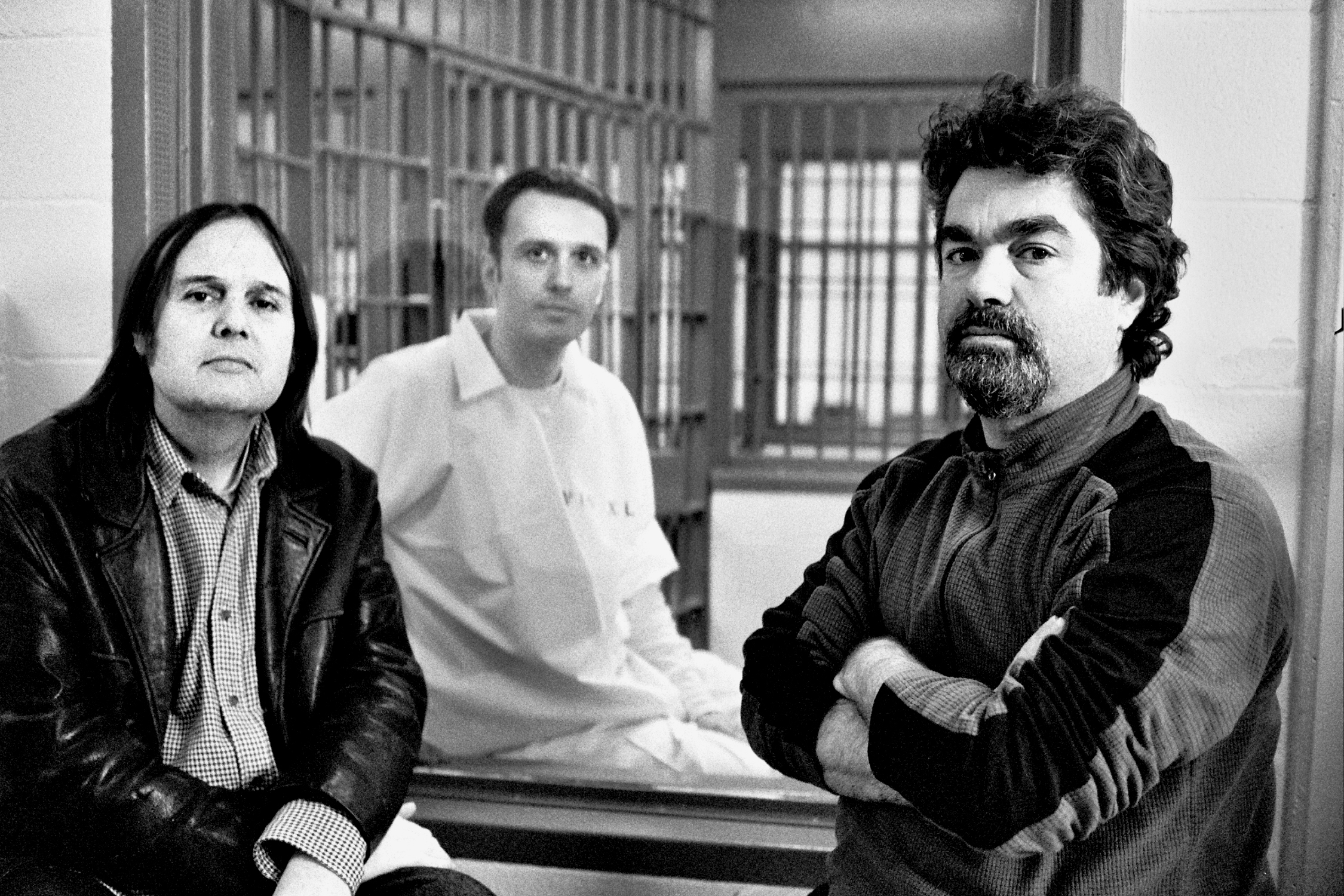

Do individuals who coordinated to destroy thousands of buildings and pieces of property nation-wide for the purpose of speaking out against perceived crimes against the environment deserve to be labeled as "terrorists"? This question is at the heart of the documentary "If a Tree Falls: A Story of the Earth Liberation Front," a surprisingly even-handed and journalistic look into the phenomenon known as "eco-terrorism."

Do individuals who coordinated to destroy thousands of buildings and pieces of property nation-wide for the purpose of speaking out against perceived crimes against the environment deserve to be labeled as "terrorists"? This question is at the heart of the documentary "If a Tree Falls: A Story of the Earth Liberation Front," a surprisingly even-handed and journalistic look into the phenomenon known as "eco-terrorism."