I don't normally watch a sequel without having seen the chapters of the story that come before them, but one of the things that makes "Paradise Lost 3: Purgatory" so good is the fact that having seen the two previous films in this documentary series is not necessary.

I don't normally watch a sequel without having seen the chapters of the story that come before them, but one of the things that makes "Paradise Lost 3: Purgatory" so good is the fact that having seen the two previous films in this documentary series is not necessary. I have not seen 1996's "Paradise Lost: The Child Murders at Robin Hood Hills," nor its 2000 follow-up, "Paradise Lost 2: Revelations," but "Purgatory" quickly gets viewers up to speed with the back story of the West Memphis Three, a story that seems to be among the most compelling true crime stories of the past 50 years in the minds and imaginations of many Americans. I was, sadly, only peripherally aware of the details of the 1993 murders of three eight-year-old boys and the convictions of the three teens who are now considered to be innocent of those murders.

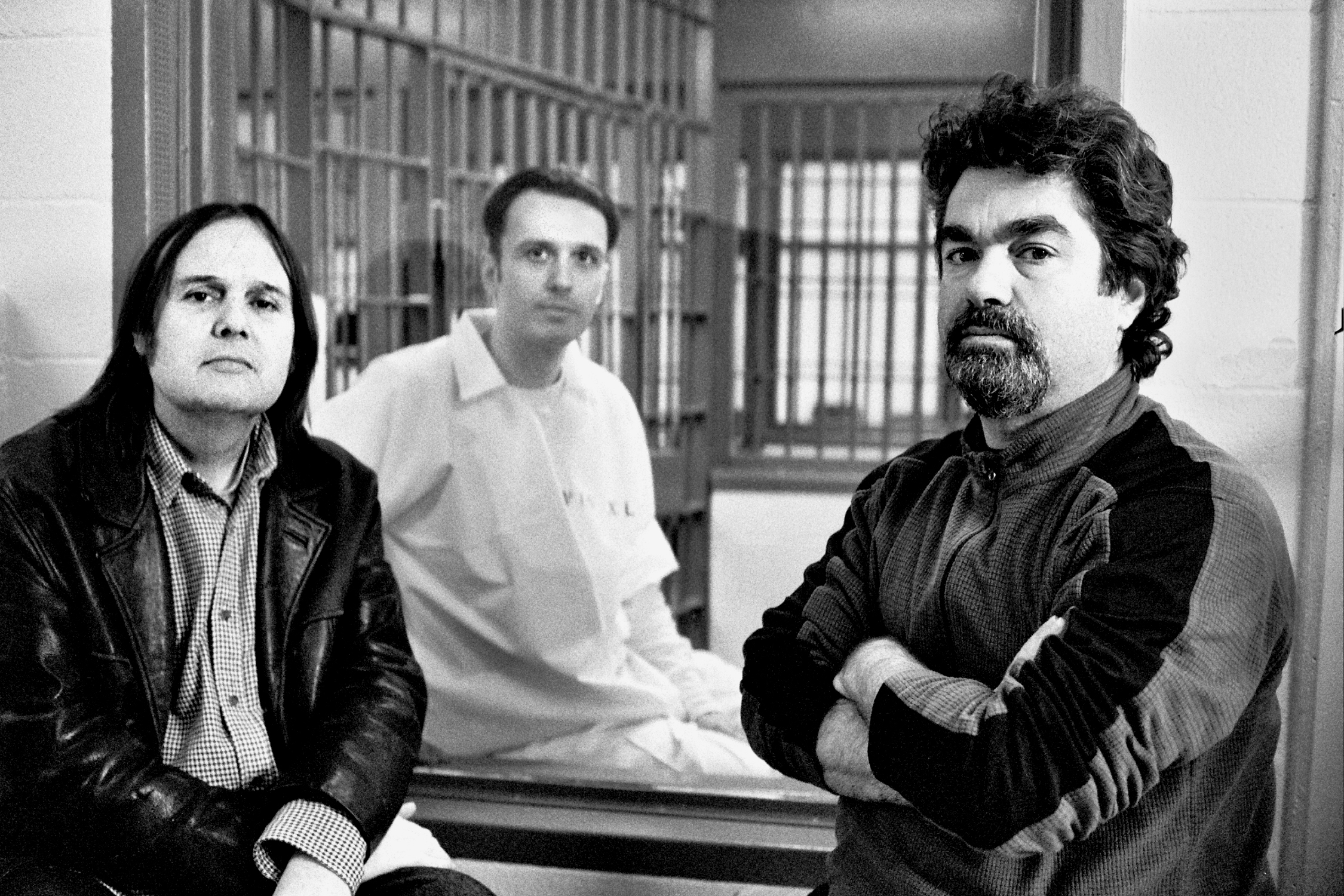

But the story is clearly compelling enough - and the sense of injustice by many was so strong - that filmmakers Joe Berlinger and Bruce Sinofsky (who have filmed everything from the Metallica documentary "Some Kind of Monster" to Oprah's current O Network program "Master Class") have apparently made keeping up with the story of the wrongfully-convicted Jason Baldwin, Damien Echols and Jessie Miskelly their cinematic life's mission.

Without having seen those previous films, I can only assume that the history Berlinger and Sinofsky have, not only with the details of this case but with the three men in jail themselves, is what allows "Paradise Lost 3: Purgatory" to be the compelling documentary that it is. This is not objective documentary filmmaking; its creators clearly believe that the three men were wrongfully committed of the killings. Nor does it go to Michael Moore-style extremes in impressing a version of what did happen on audiences (though it certainly offers up a potential suspect with more than a slight subtlety).

Like the two installments before it, this film is a part of HBO's documentary series. It showcases a decades-long persistence on the part of the filmmakers in tracing the journey of how Baldwin, Echols and Miskelly were arrested for the murders of three boys in Arkansas, railroaded into false confessions, and tried as practicing satanists, a tactic that is surprisingly convincing at times. Indeed, one of the things the film does most effectively, at least in my mind, is helps me rush to the judgment that the three young men appear to be guilty before proving to me that they are innocent. I know that viewers who arrive to this viewing experience with more information about the case than I did probably won't take this same mental journey as I did, but I was shocked and embarassed by how much of perception of their guilt was based on their appearances. They looked guilty to me. Shame on me.

I read Roger Ebert's reviews of this film and its previous chapters to get a sense of what versions of the story each previous film told, and Ebert mentions that the second film pulls out one of the slain boys' stepfathers, John Mark Byers, as the potential real killer. It is an added thrill, I'm sure, to viewers who have followed the whole story to find that in this third installment, the attention turns from Byers toward another step-father, Terry Hobbs, who is linked to the crime scene through the DNA testing of a hair.

This same DNA testing is what ultimately causes the state of Arkansas to realize that Baldwin, Echols and Miskelly did not kill the boys. They call a hearing with shocking speed after the DNA results arrive (this happened just about a year ago) and agree to set the men free under the condition of an asinine plea strategy that requires the men to essentially say "I didn't do it but I'm pleading guilty." The logic, twisted as it is to us, is that by entering this plea, the state of Arkansas is, theoretically, protected from having wrongfully jailed these men for 17 years. They can claim that the time served by the men - including one, Echols, who was on death row - was sufficient for the crime by virtue of those guilty pleas.

But Berlinger and Sinofsky are not subtle in allowing those filmed here to point out that just because these innocent men are now free doesn't mean that justice was served. Jason Baldwin even explicitly states that he might have more luck outside of jail than in getting something done, indicating that this story is not over. And while I'm not sure whether or not I'd enjoy reaching back to watch the first two Paradise Lost films, I'd certainly look forward to a fourth installment in which the now-freed men pursue the clearing of their name and go after the flawed justice system and the state of Arkansas. I'm sure that story is in the works.

Cinematically, "Paradise Lost 3" is frequently blunt, which means that you should be forewarned that it can be unwatchably gruesome in spots, particularly when it plainly offers up images from the crime scene. They are wincingly terrible to look at, but arguably necessary as well.

And we now know not only that the case of the West Memphis Three not only attracted the attention of rock stars like Eddie Vedder and the Dixie Chicks and actors like Johnny Depp (all of whom briefly appear in the film footage) but also Hollywood. Director Peter Jackson has just produced and released "West of Memphis," yet another documentary on the subject (this one directed by Amy Berg).

Do we need another film about this case as it stands right now? I don't know. I find it hard to imagine that anyone could tell the story better than these two men who have followed it so passionately from the beginning. "Paradise Lost 3: Purgatory" is now nominated for the Academy Award for Best Documentary Feature. And after having told the story for over 15 years, that accolade feels well-deserved.

3.5 out of 4

No comments:

Post a Comment