And here begins the stampede of Oscar-wannabe films for 2010! I begin my journey this holiday season with 127 HOURS, the true story of Aron Ralston, a rock climber and cave explorer who, in 2003, ventured out to his favorite spot in Utah from his Colorado home without letting anyone know where he was going and ended up, literally, stuck between a rock and a hard place. (Though I'm above a cliche like this, I include it here because "Between a Rock and a Hard Place" is actually the name of Ralston's memoir about his experience.

Director Danny Boyle re-teams with much of his "Slumdog Millionaire" production crew. Writer Simon Beaufoy, composer A.R. Rahman, and cinematographer Anthony Dod Mantle all set down their Oscars (along with Boyle's double-fisted wins) to make another one together. And the movie is, in many ways and for different reasons, every bit as good as that Best Picture winner.

I certainly am not the first - and won't be the last - to compare 127 HOURS to "Cast Away." No other film in recent memory has parallels as strong. Both films hand over their screen time to, essentially, one actor. And both are tales of unthinkable survival in the depths of unimaginable despair. But 127 HOURS is better than "Cast Away" because it requires even more creativity on the part of the director. It's almost an exercise in filming something unfilmable. Tom Hanks might have been stranded on a desert island, but he had the whole island to walk around, and he had his friend Wilson, the volleyball. The fact that he wouldn't open that undelivered UPS package, which jokingly could have contained one or more solutions to his problems, was his fault!

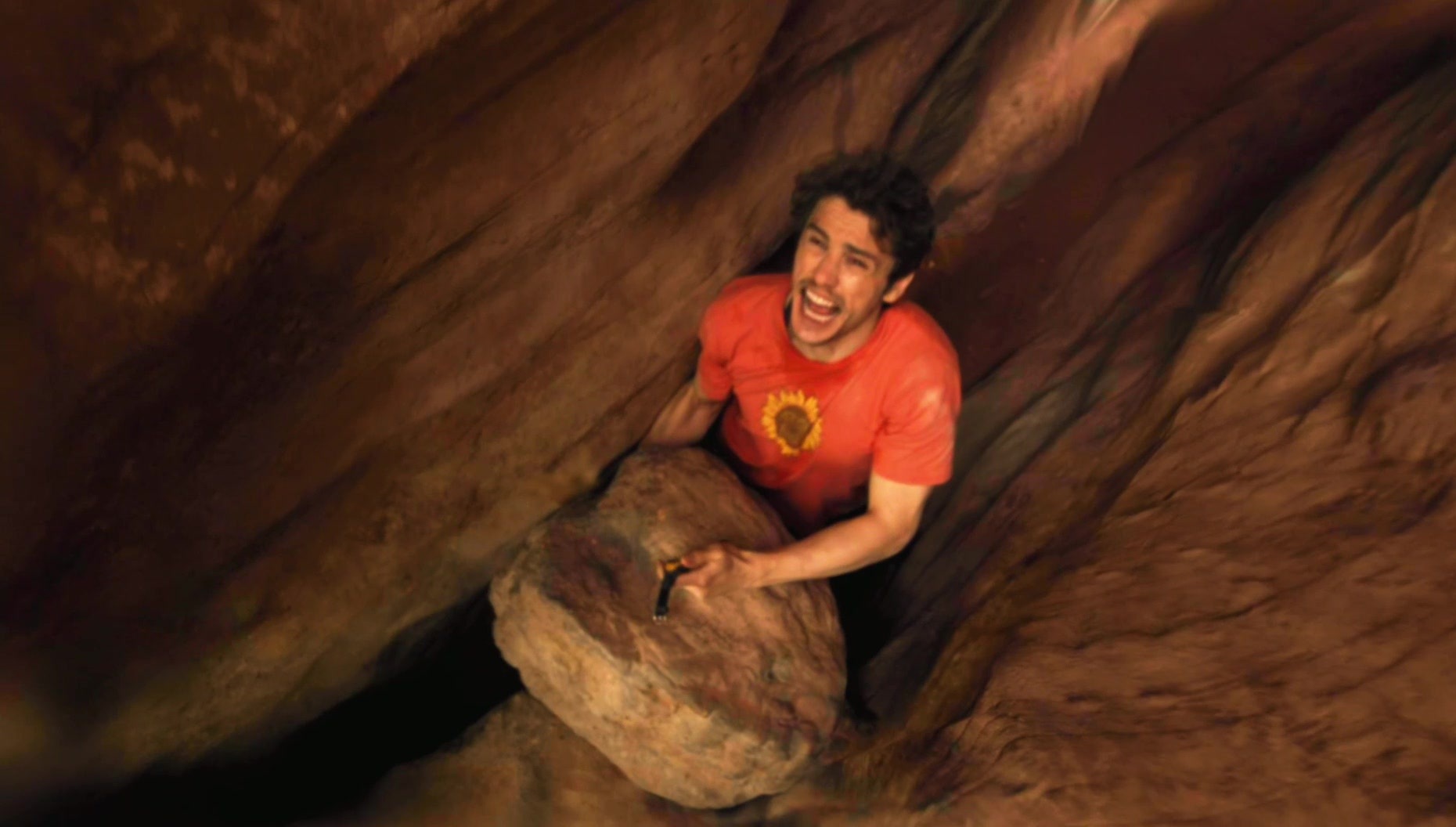

By comparison, 127 HOURS starts with a frantically juttering visual opening as prologue but then kicks in even more so creatively once star James Franco finds himself trapped in a canyon when his right arm is pinched between a canyon wall and a fallen boulder. Surprisingly, Boyle's kinetic, frantic directorial style turns out to be an unlikely perfect fit for a story that is inherently low on action, at least once the accident occurs. And what is perhaps even more incredible is the way the film builds in suspense, palpably so, when the payoff of the suspense is a moment the audience already knows about going in. That moment, of course, is the one in which Ralston decides to cut off a part of his own arm in hopes of escaping his more than five-day ordeal.

James Franco gives an award-worthy performance. He starts off as a cocky stoner-jock with charm enough to talk two female hikers into cave diving into a postcard-perfect hot spring. But his performance runs deeper. Franco creates the sense that Ralston, despite his charm with these ladies, is most comfortable when he's alone with the nature he appreciates so much. And it is not until that nature ultimately betrays him that he doesn't appreciate that solitude. (It's worth mentioning that the real Ralston continues to climb, dive and explore and most likely does not see his accident as the kind of betrayal I spoke of it as.) Once Franco is alone onscreen, he is a revelation, demonstrating stages of grief from denial to acceptance, and everything in between. Anyone who might have written this actor off as just another carefree twentysomething will be singing another tune after seeing this film.

Those who follow the Oscars can prepare for a slew of technical nominations for this film. Chief among them, I suspect, will be recognitions for the work of the sound team. For as gruesome as the images are of Ralston's self-amputation (and believe me, I turned away frequently, winced audibly and at one point shoved my knee into my mouth), it is a sound that provides the audience with its biggest, most adrenaline-filled and panicked gasp. I'm not going to say what that sound was because you can probably figure it out, but I will say that I could physically feel my heart rate DOUBLE at that moment. I might even go so far as to say that I broke out into a sweat. If nothing else, I was physically exhausted from watching a movie about a guy who wasn't moving. How is that possible?

And, of course, Boyle's name is deserving of repeat recognition as a director. I am often annoyed by the overly-hyper camera movement and trickery of some of today's ADD-influenced filmmakers, and there are a few moments in 127 HOURS that gave me a headache. But Boyle is not simply a stylist. He certainly IS a stylist, but he's also a storyteller. And he uses the camera here to get inside of Ralston's head, creating the film's real adventure. When Ralston runs low enough on water, for instance, Boyle gives us a trippy, commercial-like soft drink montage. Boyle provides the movement that the story inherently lacks, and the combination of the static plot and Boyle's energy is potent and perfect.

Don't ask how a movie about a guy stuck between rocks is exciting, because it is. Don't ask how a Canon camcorder can maintain enough battery life to keep Ralston company over five days as a portable player and video journal, because it does. And don't think you won't get through 127 HOURS without gasping for your own breath, because you won't. This is pure energy filmmaking. And you will leave the theatre thankful for your appendages and sunlight. Not to mention the fact that you will feel like you've just witnessed the story of one of the strongest human beings you've ever been exposed to.

4.0 out of 4

No comments:

Post a Comment